Preventing mother to child transmission

Hepatitis B virus can be passed from mother to child and result in long term hepatitis B infection in the child. This is known as ‘vertical transmission’. Vertical transmission may occur during pregnancy or the perinatal period. Most vertical transmission occurs at or near the time of birth [1], rarely transmission can occur in-utero. Worldwide, mother to child transmission is responsible for most infections of hepatitis B and the majority of complications of hepatitis B infection occur in those who acquired infection through vertical transmission.

Africa has lagged behind in the implementation of ways to prevent HBV mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) [2,3,4]. This is despite the number of infections in the community being high (>8%) and the African region having the greatest number of HBV infections in children under 5 years of age, estimated at 2.3% in 2017 [5,6]. It is a shocking fact that less than 10% of African newborns receive HBV vaccine at birth [7,8] and less than 1% of pregnant women are screened and treated in the WHO Africa region [9].

Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) is important because most hepatitis B complications occur in those who were infected by vertical transmission [10,11]. These complications include liver failure, cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer (HCC).

In the vast majority of infected newborns (>90%), the immune system is not able to clear the infection and the virus continues to multiply in the body. This is known as chronic infection. Those with chronic infection are at risk of liver cancer, scarring of the liver and liver failure. This contrasts with infection in older people where eg. in young adults infection only becomes chronic in around 1-6% of people.

HBV MTCT occurs primarily through contact with maternal fluids during passage through the genital tract, "in utero" (before birth) transmission is rare. Transmission through breastfeeding is not proven to occur.

Mother to child transmission can be prevented

Several different strategies for HBV PMTCT are recommended by the WHO [12]:

Routine screening of all pregnant women for hepatitis B and follow up by the health care system for those who are infected ;

Treatment of mothers at high risk of HBV MTCT due to a high amount of virus in the blood (HBV viral load >200,000 IU/ml);

HBV birth dose vaccine. This should be administered within the first 24 hours of life;

Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HIBG) injection for the infant at birth.

Together, these strategies provide maximum effectiveness for HBV PMTCT.

Hepatitis B vaccine has been available since 1982 - it is safe, effective and inexpensive. The wide implementation of this vaccine has dramatically reduced hepatitis B transmission. As a major public health success, a reduction in new infections in children under five has been achieved, with a global prevalence in 2015 of 1.3% compared to 4.7% reported in 2000 for this population [15, 16].

All infants (in particular those born to infected mothers) should receive the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine at birth, preferably within 24-hours of delivery – this has been a recommendation from the WHO since 2009.

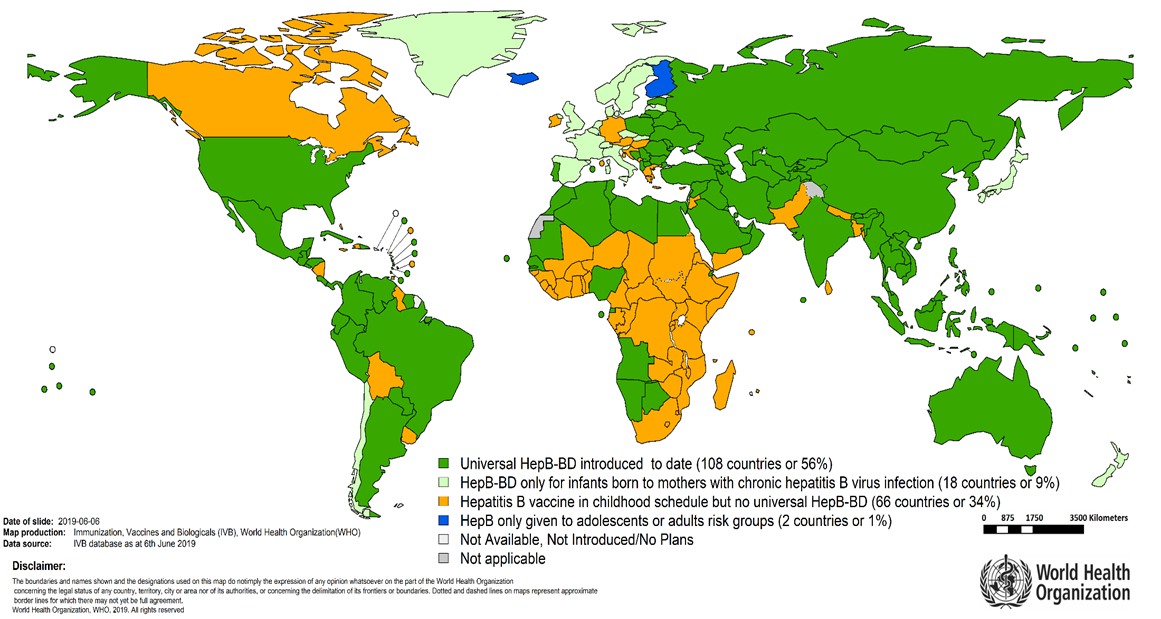

The implementation of this recommendation has been slow in the African region - only about 6% of infants receive timely birth dose vaccination with only 15 countries in 2022, that have introduced vaccination at birth (Angola, Botswana, Cape Verde, Gambia, Namibia, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Morocco, Algeria, Mauritania, Côte d'Ivoire, Benin, Equatorial Guinea, Burkina Faso).

The problems with the vaccination cold chain and how it is preventing the roll out of birth dose vaccination need attention, as does the use of novel technologies like compact pre-filled auto-disposable injection devices in order to get vaccination to infants as soon as possible after delivery [17].

Hepatitis B immunoglobulin

Vaccination does not prevent infection in all hepatitis B-exposed babies. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) –provides short-term, immediate protection to HBV-exposed babies born to mothers who are at high risk of transmitting to their infants.

HBIG is expensive and is difficult to access in many resource poor areas because of the infrastructure needed to store, transport and administer it.

Peripartum antiviral prophylaxis

Antiviral medication like tenofovir prescribed during pregnancy decreases the level of hepatitis B virus in the blood and so reduces the risk of transmission to the infant.

Tenofovir (TDF) is safe to use during pregnancy but is not available to all pregnant women who need it.

One of the main obstacles to putting women on treatment in Africa is the difficulty to identify those most at risk of onward transmission. Currently HBV viral load testing is too expensive to offer to those who need it most [18].

Hepatitis B antenatal screening

Antenatal screening for hepatitis B infection is recommended by the WHO, in areas where the number of people with hepatitis B is more than 2%.

This screening, performed in the first trimester, should form part of the triple elimination strategy to eliminate mother to child transmission of HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B.

Point of care rapid tests can be used to identify women at risk of transmitting these infections to their infants so that targeted prevention or treatment can be implemented [19].

Antenatal screening offers a unique opportunity to prevent not only mother-to-child transmission, but also to offer vaccination to the wider family [20].

Education of health care workers

Pregnant women rely on their health care providers both to ensure they have access to education and to the therapy they need. Healthcare programmes taregetting maternal and child health should ensure that health care workers can provide women with the hepatitis B literacy they need in order to make informed choices and seek further support if needed.

Triple Elimination (HBV, syphilis and HIV)

The WHO has committed itself to the elimination of mother to child transmission (EMTCT) of HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B as a public health priority. The Triple EMTCT initiative focuses on a joined-up approach to improving the health outcomes for mothers and their children [21].

The WHO and its partners have committed to provide support for strengthening health systems to ensure person-centred care that respects and protects the rights of women with any of these conditions and to ensure that women are meaningfully involved in health programme planning and service delivery.

In order to stop the cycle of these infections from mother to child we need to work together to ensure:

· every African pregnant woman is screened for HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B

· every HIV infected African woman has access to treatment

· every African woman who is infected with syphilis has access to treatment

· every African woman at high risk of HBV transmission has access to tenofovir and her infant to HBIG

· every African child has access to hepatitis B vaccination within 24hours of delivery

References

1- Broderick AL, Jonas MM. Hepatitis B in children. Semin Liver Dis. 2003 Feb;23(1):59-68.

2- Andersson MI, Rajbhandari R, Kew MC, Vento S, Preiser W, Hoepelman AI, Theron G, Cotton M, Cohn J, Glebe D, Lesi O, Thursz M, Peters M, Chung R, Wiysonge C. Mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus in sub-Saharan Africa: time to act. Lancet Glob Health. 2015 Jul;3(7):e358-9.

3- Shimakawa Y, Toure-Kane C, Mendy M, Thursz M, Lemoine M. Mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016; 16(1):19–20.

4- Keane E, Funk AL, Shimakawa Y. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the risk of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Nov; 44(10):1005–17.

5- Shimakawa Y, Lemoine M, Njai HF, Bottomley C, Ndow G, Goldin RD et al. Natural history of chronic HBV infection in West Africa: a longitudinal population-based study from The Gambia. Gut. 2016;65(12):2007-2016.

6- Nayagam S, Thursz M, Sicuri E, Conteh L, Wiktor S, Low-Beer D, et al. Requirements for global elimination of hepatitis B: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Dec; 16(12):1399–408.

7- Bassoum O, Kimura M, Tal Dia A, Lemoine M, Shimakawa Y. Coverage and Timeliness of Birth Dose Vaccination in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines. 2020 Jun 11; 8(2):301.

8- Polaris Observatory Collaborators. Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(6):383-403.

9- World Health Organization. https://whohbsagdashboard.surge.sh/# global-strategies

10- Shimakawa Y, Yan H-J, Tsuchiya N, Bottomley C, Hall AJ. Association of early age at establishment of chronic hepatitis B infection with persistent viral replication, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. PLoS One.2013; 8(7):1-12.

11- Shimakawa Y, Lemoine M, Bottomley C, et al. Birth order and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic carriers of hepatitis B virus: a case-control study in The Gambia. Liver Int. 2015;35:2318-2326.

12- Howell J, Lemoine M, Thursz M. (2014).Prevention of materno-foetal transmission of hepatitis B in sub-saharan Africa: the evidence, current practice and future challenges. J Viral Hepat.21:381-96.

13- Lee C, Gong Y, Brok J, Boxall EH, Gluud C. Hepatitis B immunisation for newborn infants of hepatitis B surface antigen-positive mothers, Cochrane Database Syst Rev(2006). https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/Lee_review_HepBinf_CD004790.pdf?ua=1

14- Ekra D, Herbinger K-H, Konate S, Leblond A, Fretz C, Cilote V, et al. A non-randomized vaccine effectiveness trial of accelerated infant hepatitis B immunization schedules with a first dose at birth or age 6 weeks in Côte d’Ivoire. Vaccine. 2008;26:2753–61.

15- Global Hepatitis Report, Organisation mondiale de la Santé, Genève, 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255016/1/9789241565455-eng.pdf?ua=1, consulté en mai 2021.

16- World Health Organization. https://whohbsagdashboard.surge.sh/# global-strategies

17- Seaman CP, Morgan C, Howell J, Xiao Y, Spearman CW, Sonderup M, Lesi O, Andersson MI, Hellard ME, Scott N. Use of controlled temperature chain and compact prefilled auto-disable devices to reach 2030 hepatitis B birth dose vaccination targets in LMICs: a modelling and cost-optimisation study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020 Jul;8(7):e931-e941

18- Guingane AN, Bougouma A, Sombie R, King R, Nagot N, Meda N, et al. Identifying gaps across the cascade of care for the prevention of HBV mother-to-child transmission in Burkina Faso: findings from the real world. Liver Int. 2020 Oct;40(10):2367–76.

19- Chotun N, Preiser W, van Rensburg CJ, Fernandez P, Theron GB, Glebe D, Andersson MI. Point-of-care screening for hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women at an antenatal clinic: A South African experience. PLoS One. 2017 Jul 21;12(7):e0181267

20- Guingané, Alice Nanelin, Kaboré, Rémi, Shimakawa, Yusuke, Somé, Eric Nagaonlé, Kania, Dramane. et al. (2022). Screening for Hepatitis B in partners and children of women positive for surface antigen, Burkina Faso. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 100 (4), 256 - 267.

21- Cohn J, Owiredu MN, Taylor MM, Easterbrook P, Lesi O, Francoise B, Broyles LN, Mushavi A, Van Holten J, Ngugi C, Cui F, Zachary D, Hailu S, Tsiouris F, Andersson M, Mbori-Ngacha D, Jallow W, Essajee S, Ross AL, Bailey R, Shah J, Doherty MM. Eliminating mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis and hepatitis B in sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2021 Apr 1;99(4):287-295

Authors

Dr Alice Guingane, Hepatogastroenterologist, Hospital Center University De Bogodogo, Ougagdougou, Burkina Faso

Dr Monique Andersson, Consultant in Clinical Infection, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust, Oxford, United Kingdom